2020 Other noteworthy articles: ShoutOutLA, interview; Singular Art; Cafe Review, profile; Studio C, profile; Art & Cake “Over 65”; The Gardian “Art During Covid-19; Artist Portfolio Magazine, profile, artwork spread; Kellogg Gallery #artistchallenge2020; How We Are, profile;

Dave Barton

Light & Space Through Time: Karrie Ross

Catalog Essay: 2019 Blackboard Gallery

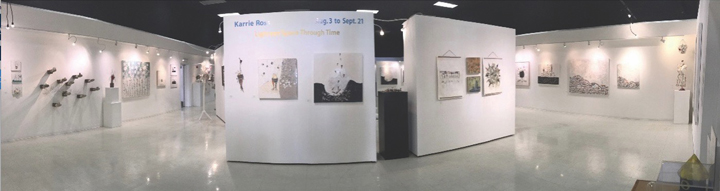

Entrance to Gallery:

Blackboard Gallery, Solo Exhibition for Karrie Ross; August 3rd thru September 21st, 2019. Light and Space Through Time

The gouache white of an eggshell.

Its surface is not smooth, what should be soft to the touch is marred by tiny dips and pits in its landscape.

The blank slate—like any idea—is rarely even, the thickness of the shell allowing for pale gradations of color, exacerbated by whatever light touches it.

It’s frail.

It’s thin.

Protecting the soft yolk inside.

Fertilized, in a nest, it is the beginning of life.

Unfertilized, on a plate, it’s breakfast.

A metaphor for ideas.

For love.

For female sexuality.

It’s our head.

It’s our heart.

Both easily broken.

Entrance to Gallery:

Blackboard Gallery, Solo Exhibition for Karrie Ross; August 3rd thru September 21st, 2019. Light and Space Through Time

The egg is in the center of Karrie Ross’s world.

Especially in her 2019 work.

While the exhibition is a retrospective of sorts, the image of the egg becomes its vantage point. After a crippling 2018 brain/body injury suffered in a fall, Ross’s work in 2019 becomes her celebration of the broken recovered.

It’s a totem of joy, a return to spontaneity and whimsy, an obsessive recurring visualization of time passing aging and the possibilities of new growth and life after trauma.

First, there’s injury.

The Egg Inside canvas splits in two and separates the ovoid shape, as the top dark half rises into the sky like a long malevolent rocket, weaving out of control, abandoning the more colorful, patterned lower half. Climb the Highest Mountain’s damaged egg leaves a deep blue phallic trail behind it, its shell broken into shards and ungainly sharp pieces. As it tries to move upward in its wounded state, it’s stymied in its tracks by the bars above it.

Second, the survival.

Each of Ross’s trio of mixed media on panel pieces—Catch, The Egg with Gingko Tea or A Frog In The Works!, and The Egg of the Golden Veil–suggests the beginnings of healing. The first has a hand bursting from the ground to catch an already-shattered egg in mid-air, preventing further damage; the second shows a pair of hands placing and steadying a haplessly-reassembled egg in a nest (a pair of amphibial eyes poking from one corner), as a lone human figure chained at the neck to the side of the panel, watches without emotion, disassociated from the action; the third ovoid, broken and bandaged, passes through a tricky piece of gold netting, successfully arriving on the other side without snagging its edges in the process.

Then there’s the hope.

In What Lays Beneath, the blackened shadow of a buried egg in a hill appears safe and secure from the rain of arrows attempting to pierce it. The ground it lies in stalls and stops their movement, a reassuring statement about perseverance, the hill looking like it’s shrugging off the spikes coming its way. An egg lies comfortably in a soft black crater in Passing Through. As the tips of arrows drop from the sky and bounce off its shell, they collect into a fine-pointed pool of checkered color below. The slings and arrows of the past creating a prickly second nest within a nest. Using similar imagery in That’s a Hard One!, a tree has grown from a still intact egg, a human figure triumphantly in the foreground, on top of a stack of the arrows. In the row of three black hills in Where IS the Egg?, the shape is hidden within one of the hills, a hand reaching to pluck it, as if playing a shell game. Playing with the theme of continuance through adversity, the mixed media on panel Wondering Why the Right Words Never Come reveals a human figure with a black hole where their heart would be, the egg and ensuing arrows fan out over its head like the halo on a saint. In There are Moments of Pretend, an egg rests in the dip of a black canyon: three figures standing inside, like visitors from another planet, as a gathering of other figures awaits their arrival.

The softening of trauma and the reduction of fear.

Ross reduces healing to a divine process of balance and elimination, as an egg teeters on the profile of a face in It’s A Balancing Act; another profile, facing down from the heavens, lets an egg spew out of its mouth onto a monolithic black hill, tiny trees lining its surface. In Going Within, the emitted egg is assisted by a hand helping to guide it into place.

Ross takes us back to the comfort of childhood with her Eggs in a Basket, as a flat wood surface and support piece uses wire, paper, paint and cellophane to suggest an Easter gift, the blues and pinks and yellows reading like the wrapping on Lindt truffle candies. Her stuffed fabric versions turn the eggs into items resembling plush ornaments (Lost Eggs), or surrounds them with security, a coiled snake cocoon hugging them safe inside (Egg Rolled).

There’s new growth.

THE EGG!, like Eggs in a Basket, a flat surface with a support piece piercing the middle lower half, sprouts eleven tiny wire stalks, abstracted flower beads budding at the end of the tiny wire stalks. Within the mixed media boundaries of Bougainvilleggs, Ross gives us new life budding from the shells. It’s not the baby chicks you might expect, but wiry green sprouts wriggling their way through the shell out into the open air. The dark ground they rest on is funereal, but made less so by a celebratory spread of loose red flower petals, shorn of the bougainvillea’s thorny branches. Sprouting Egg also offers us new life, again without interference, the seedling blooming into a fan. In Cloud Egglas, two hands reach out to lift and embrace a pair of profiles emerging from an egg, one spitting and extending a hand with a tiny gift, another with legs akimbo; the dreaminess of the gesture gently protective.

Finally, joy.

Five eggs playfully tumble about in the palm of a hand, the topmost egg raising its hand to collect or support a smaller, legless egg to the sky in You Can Check Out Any Time You Like.

Leaving behind the darker hints of some of the other work, the image in Jumping Off offers the viewer a moment entirely appropriate for a fine art children’s book: A small pink egg perches on a larger crimson egg, both held airborne by the gentle exhalation of a profiled face.

That lone, impossibly surreal image leaves the viewer with a smile, but also with the idea of Ross breathing new, complex life into something that many of us never even notice. It’s not just a memorable image, it’s the artist’s kiss.

Dave Barton, December 2019

Dave Barton has written extensively about art, theatre, and politics for the past twenty years, in a variety of newspapers and magazines. He was the OC WEEKLY art critic from 2009-2019.

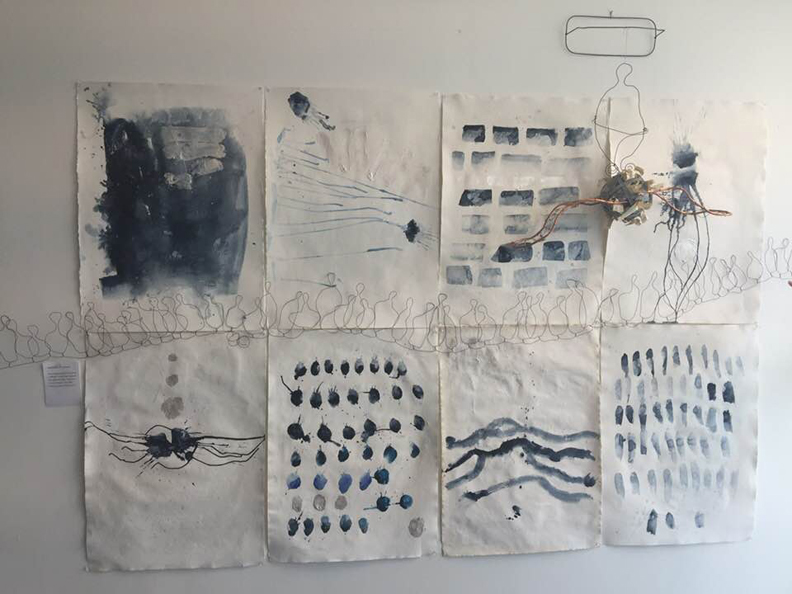

Mood Indigo

Essay By Eve Wood

May, 2018

The elegant and painterly drawings that comprise Karrie Ross’ most recent Indigo series are unsettling in their rawness and emotional tenor, yet sustain a mutable and effortless power. Working in a variety of media including acrylic and watercolor, these elegantly luminous drawings are deceptively simple. Mining the same territories as artists like Cy Twombly and Joan Mitchell, Ross utilizes a relatively simple color palette in order to create more complicated relationships between structural forms. At once loose and oddly rigid, the paint as it is applied here appears both viscous and fluid, the small blue dots appearing to float in the surrounding negative space like small planets in an ever expanding galaxy.

True indigo derives from the Indigofera plant, which is grown in tropical regions. Historically as well as metaphorically, the color has variegated meaning and represents the power of perception and intuition. It is said to promote concentration in times of deep introspection and trauma. Ross contrives to balance this powerful color against the simplicity of basic shapes and forms derived from imagination, intimating a hidden narrative. For example, in one drawing, we are given three lines that appear to buckle in on themselves, pushing out from the center to form a sort of watery boundary of deepening blue mitigated only by the surrounding negative space. Forms break free from the central shape like birds taking to the open skies, and it is these flourishes that hold our attention.

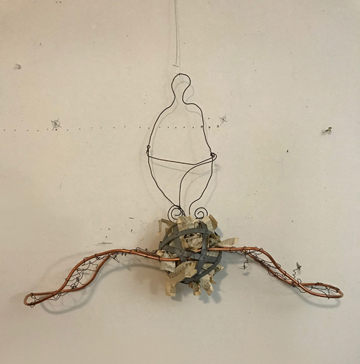

Still other images appear as color swatches that are gradient and move from dark to light and could be read as possible Rorschach like diagrams that chart various emotional cadences. There is also an implied relationship between the drawings and the sculpture wherein each informs the other. The sculptures, as with the drawings are strangely enigmatic and reference language and a hidden narrative that seems to relate to the idea of flight.

The sculpture, aptly titled “Flying Ball of Words,” is filled with the leavings of language, bits and pieces of paper cut up and strategically placed inside a sphere with copper like wings. Behind this central object is the outlined figure of a man presiding over the extended copper wings. Again, as with the drawings, the sculptural works exist somewhere between restlessness and quietude, longing and inner peace, consciousness and unconscious thought, the pushing out and pulling in of desire. There is also the suggestion here of the failed attempt at flight, the hinted narrative of Icarus’ tragic end as the sculpture is pinned to the wall and unmoving, and the bound words, the final iterations of a figure doomed to die by his own insistence.

Finally, the drawings and sculptures that make up this particular body of work convey a sense of immediacy, a quickening, an urgency by their mere expressiveness as though each blue dot were a separate universe in and of itself and the fact they are in close proximity to one another further emphasizes their beauty, grace and singularity.

Eve Wood is an artist, writer of poetry, interviews, reviews for the artworld. http://www.evewood.net

Interview in Easy Reader magazine 2017, by Bondo Wyszpolski

For the exhibition in San Pedro, SBC, “The Faces Within” curated by Karrie Ross

“Karrie Ross has become fairly prominent in the local art scene, as an artist, a curator, but also for her anthologies, these being a series of books about artists with the general title of “Our Changing World: Through the Eyes of Artists.” These serve as chronicles or documents about what regional artists are thinking and exploring in their work. There are currently eight books available.”

“Karrie Ross has become fairly prominent in the local art scene, as an artist, a curator, but also for her anthologies, these being a series of books about artists with the general title of “Our Changing World: Through the Eyes of Artists.” These serve as chronicles or documents about what regional artists are thinking and exploring in their work. There are currently eight books available.”

Continue to full interview review here.

No matter who one voted for on Nov. 8, most Americans would likely now agree that the first days of Donald J. Trump’s presidency have been the most contentious, if not the most divisive, in recent memory. More so, even, than when George W. Bush snatched victory from Al Gore in 2000.

While all of this is relevant on the national stage, it’s also playing out locally with “Dear President,” the ongoing group show presented by South Bay Contemporary that not only focuses “on issues that our country faces,” but articulates “who we are, where we come from, what we stand for, and what we are against.”

Adjoining “Dear President,” and assembled in a smaller and separate room, is a second show, curated by Karrie Ross, entitled “The Faces Within.” There are 14 artists, each of whom was entrusted with a slice of canvas 15” by 30” and asked to create either the left or right side of a face that would then be paired with an opposite half done by another artist. The result is seven large paintings, 30” by 30”, comprised of two separate half-faces. Got it? What the artists were asked to represent was their emotional or physical state during the 2016 election. They were also asked to prepare a brief artist statement, many of which reveal a deep concern for where a Trump presidency could be taking us. Excerpts from several of them appear below.

Prelude to a gallery show

Karrie Ross has become fairly prominent in the local art scene, as an artist, a curator, but also for her anthologies, these being a series of books about artists with the general title of “Our Changing World: Through the Eyes of Artists.” These serve as chronicles or documents about what regional artists are thinking and exploring in their work. There are currently eight books available.

Ross is a native Californian, born in Lynwood and raised primarily in the San Fernando Valley. Her parents were talented, her father being an inventor and carpenter, her mother a florist: “She was extremely creative,” Ross says; “she taught me asymetrical appreciation. So, most anything I do, there’s very little symmetry in it, except in my graphic design.” After her first husband returned from Vietnam, Ross lived in Tacoma, Washington, came back to Los Angeles, spent three years in Vail, Colorado, had a son, a second marriage, and early last year bought a house in Gardena after a quarter century living in Mar Vista.

“I spent 40 years doing marketing and advertising in some of the larger graphic design studios and corporations in Los Angeles,” she points out. “I’ve done everything from Yellow Pages to annual reports.” For the past 15 years, Ross has been engaged in book design for self-publishing authors. And not only is she herself a published author, but she’s also a certified life coach. Although she did not attend art school or receive formal training, Ross has a distinctive style when it comes to her own creations. Years ago, to supplement her income and to help put her son through college, she took her little white tent to various “art in the park” shows in such places as Beverly Hills, Brentwood, Malibu, La Jolla and San Diego. This brought her to the attention of a company for which she produced art for reproduction, and financially it helped her for about ten years. From 2008 to 2011, Ross was connected to a membership art gallery, which proved to be an education in itself. That led her, she says, “to take a look at what everybody was doing from a standpoint of either theme or style or focus. So my curating started there, as well as my understanding a little bit more about the art world.” This also resulted in the first of her artist books, published in 2013. The theme of that book was “What Are You Saving From Extinction?” For herself, she says, “I’m saving my internal play. For another person, they’re saving the awareness of the drought. One (person) painted an old car with rust. That old car is going to go away, and so you’d like to think that this painting would have a longer life someplace.” To coincide with the book’s publication, which featured 36 artists, Ross rented a space, a pop-up gallery, and curated an exhibition.

One thing led to another, and in May of last year she sat down with Peggy Zask and said she’d like to curate a show for South Bay Contemporary should the opportunity arise. It can’t happen here. Right? “I don’t watch the news,” Ross says, “but I was getting very upset, and so emotionally I wanted to be able to express this. And I was feeling that I wasn’t alone. It’s not so much political, although the political is the antagonist.” However, “Over the last year or so the political environment has weighed heavily on everything else that we’ve done and on anything else that we do, on our decisions.”

Like the rest of us, Ross watched the debates between candidates Clinton and Trump. “Isn’t anybody else seeing this?” she asked herself. “This is the second debate and he’s still not being addressed in the way he needs to be addressed to stop this behavior.” As might be expected of a life coach, she looked at the issues the Republicans and the Democrats were presuming to discuss for the benefit of the American electorate, and she tried to see all viewpoints.

“I had come up with here’s one side and here’s the other side, the angel, the devil, the right, the wrong, the good, the bad, whatever. You can keep going into that and internalizing it where and how and why it comes.” And so this led Ross to her concept of the half-faces, which Peggy Zask agreed to exhibit in conjunction with “Dear President.” That’s how “The Faces Within” got underway. “I really wanted the show to have a dynamic of artistic focus,” Ross says. “And not one of (the artists) has the same style.” Her directions were simple, merely to explain where the eyes, the nose, the mouth, the chin, and the top of the head had to go, “so when I put it (the two halves) together it looked like a face.”

Rather interestingly, the artists were not told who they’d be partnered with. They were not even told who else was contributing to the show. They only found out at the opening. The reason for this “secrecy” was because Ross didn’t want any of these artists to be inspired or influenced by other artists, but to simply delve within to manifest their own inner feeling. Zask was impressed with how “The Faces Within” developed: “As the half-faces were delivered to the gallery,” she says, “Karrie Ross paired them to [the best of] her artistic capabilities. After they were installed she observed how each face had a dominant and a passive side. This can be perceived as a metaphor; just as two sides of a coin make a single coin, the dominant populist candidate (Trump) got all of the media attention and the passive candidate (Sanders) almost none. “As is often the case, the dominant figure (the one who makes the most noise) won, and now it’s up to all the people to rise up and save our democracy in a powerful and peaceful manner.

It should be noted that the show was not conceived as an anti-Trump show or campaign or protest. Not surprisingly that came about courtesy of the man himself. Now let’s leaf through the artists’ statements that underline what the majority of them were thinking.

We shall overcome. I’d like to foreword this section with a passage from “Imperium,” by the late Ryszard Kapuściński. Written in 1993, it’s no less relevant now: “Three plagues, three contagions, threaten the world. The first is the plague of nationalism. The second is the plague of racism. The third is the plague of religious fundamentalism. All three share one trait, a common denominator–an aggressive, and powerful, total irrationality.” And don’t simply assume that “religious fundamentalism” applies only to Islam. Christianity and Judaism are far from immune to it. These are a few yet telling excerpts, written by some of the artists to accompany their work in “The Faces Within.” They also date to before the inauguration on January 20, after which events in this country went into hyperdrive.

Vicki Barkley: “We elected a puppet, a grifter, a predator, into our most powerful office. Sixteen years ago, I believed we had done our worst. Now we see we have unlimited capacity to make mistakes, act on our basest nature, and burn down our own house rather than face history and ourselves.”

Randi Matushevitz: “My reaction to this election circulates through a variety of emotions: shock, disbelief, fear. I am avoiding hopelessness.”

Sarah Stone: “I saw an image of birds violently swarming in and out of my head, representing countless headlines, rumors, opinions, and the daily informed and uninformed media predictions.”

Anna Stump: “I will never see a woman president. I would have liked to see a woman president. I wish I had lived to see a woman president. I dreamed I could see a woman president. I never thought there would be a woman president. I hope my daughters will live to see a woman president.”

Steve Shriver: “My piece is about the clown we have hired to lead this country for the next four years. His facial expressions sum up my reaction to the election.”

Nancy Larrew, referring to the title of her work, “No One Will Believe You,” with regard to the “inner voice” that often prevents us from speaking up after being personally assaulted: “This election process has amplified that voice by allowing a self-proclaimed celebrity, pussy-grabbing misogynist’s behavior to be normalized into ‘locker (room) talk” while allowing its implications to be overlooked under the pretense of making America great again.”

Scott Meskill’s statement is comprised of stark, single words that proceed from Hacking, Russians, Deniability, Lies, Hate, Bigotry, to Bankers, Power, Corruption, and lastly to Learn, Grow, Hope, Plan, Fight!

Some of the artists submitted follow-up comments this week: Randi Matushevitz: “America is about Freedom. Let’s be forceful by not turning a blind eye.” And Malka Nediva: “I can say that I am only getting more and more worried, and I think it is scary what’s going on. Really scary!”

We should wish our government well, of course, but to what point? With great power comes great responsibility, and that means prudence and clear-thinking. To date, we’ve seen very little of this. Will the Republicans in our nation’s capitol speak up and speak out, or is party loyalty more important to them than loyalty to their country?

The Faces Within and Dear President are open this evening during the First Thursday Art Walk at South Bay Contemporary in San Pedro. An artists’ talk is scheduled for the day both shows close.

Artist Karrie Ross is a survivor.

Review: Art Critic, Dave Barton, 2017

In person, you can see it in her eyes: the bright, weary glare of a woman who has been playing the boy’s club art game for more years than it’s polite to ask. I could see it in my recent studio visit with her. You can see it in the numerous works featured on her website.

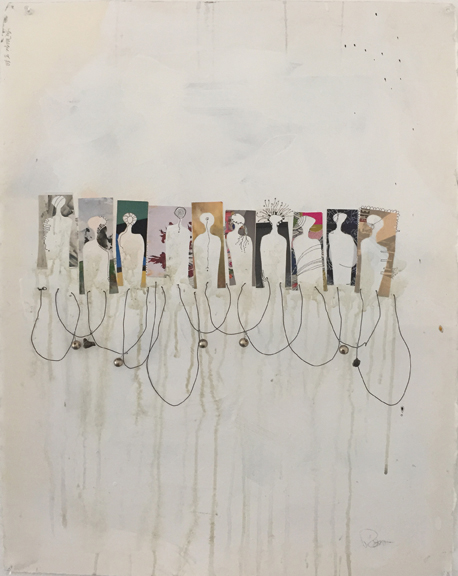

Five figures—wood templates for a planned series of metal sculptures—stand in front of the window, sun bursting through the gaping holes in the middle of each, as if they’ve just faced a firing squad. Wire and bead designs hang inside the holes; Tao symbols, wheels, eggs, and flowers all standing in for viscera. In place of faces, more beaded glass gives us eyes, noses, the suggestion of a wan smile; fright wig hair springing from the heads painted to represent Wu Xing (Elements). Given a little refinement and the more solid structure that metal will bring, one can easily imagine them whirling on spinners as kinetic pieces.

The ONE: 4″x4″ canvas’ collage images with The ONE removed out on a stick to be inserted by hand in perspective and participation

Other idiosyncratic figures, still alone, but grouped together in The ONE: Boxed, looking like solid bricks in a wall. The more than a dozen small boxes, exquisite corpses covered with vibrant card art created by another artist and repurposed by Ross, feature a lone figure attached at the top or side. Solitary, defiant, the planted figure often defying gravity, and never too far away from its origin: Cut from the front of the card art, it has left a bright and beautiful Hiroshima shadow underneath.

That lonely figure standing amid a chaotic background is a continuing theme in her latest works on paper. In Nature: The ONE with Water, the armless figure stands in water, towering high above the tiny wave breaks below. Her tapering neck—bright, lightbulb head glowing gold—sways and bends dangerously as the paint-spattered wind whips her about, her trunk, filled with a visible brown miasmic grief, firmly rooted in place.

In another, Where is the Water?, a smaller figure is seen buried from the waist up (ala Samuel Beckett’s Winnie in Happy Days) in a similar watery. Assailed from above by flying, pizza slice-shaped darts—some aimed at her, others seemingly deflected by her circular wings—she still glows, a silver statue of strength.

In the mixed-media The Magic of Ten, ten of the outlined figures stand in an uneven row against a background of dripped paint that looks like a combination of watery mold and running mascara. Instead of a single figure going it alone, Ross has linked the figures with wire, making them more of a chain gang, suggesting strength through a united front.

Being targeted by the slings and arrows of life covers a lot of artistic ground for many artists: the fears of not being seen; the long hours in a studio by oneself; the accompanying depression that comes with never making quite enough money doing what you love; having to take meaningless side gigs to make ends meet. It can feel like one is continually beset.

Ross’ work is a grand statement that she’s around, fighting, despite what life has handed out to her (and us, by extension). Instead of being crushed under that weight—as so many of us have—she is extending an open hand, and saying stand up, come with me, we’re safer in numbers.

Dave Barton Has interviewed artists from punk rock photographer Edward Colver to monologist Mike Daisey, playwright Joe Penhall to culture jammer Ron English. He writes art reviews for the OC Weekly for over twenty years, the last eight as their lead art critic.

“A Catalyst of Meaning: The Art of Karrie Ross”

IMPACT OF LIFE (catalog and video for LA Artcore August, 2014)

By Jill Thayer, Ph.D.

For centuries, artists have explored the conceptual boundaries of art and science, such as Da Vinci, whose empirical methodologies revealed the creative discoveries of imagination and curiosity. Those mechanisms of gestalt inspired many in the notions of visual perception and, the reality of being. The psychological phenomena that occurred throughout the process would open the door for wonderers to come. Karrie Ross is an artist who sees the realms of existence through a multi-faceted lens: energy, science, participation, conversations, and being seen are influencing constructs of her work. She notes that, “metaphorical representations create a ‘safe’ place for the viewer to experience a flow and connection from their interaction with the art, discovering that they are part of a bigger whole.” This intent engages a reflexivity between viewer and artist, as Ross defines her process of discovery as one that is intertwined with learning about matter itself, such as the molecular vibrations of an atom that require energy in transitions––and that everything has a frequency, which the universe reciprocates. She adds, “I paint with abandon, and my belief system is that we’re all connected through the vibrational energy of the earth that is natural.”

For centuries, artists have explored the conceptual boundaries of art and science, such as Da Vinci, whose empirical methodologies revealed the creative discoveries of imagination and curiosity. Those mechanisms of gestalt inspired many in the notions of visual perception and, the reality of being. The psychological phenomena that occurred throughout the process would open the door for wonderers to come. Karrie Ross is an artist who sees the realms of existence through a multi-faceted lens: energy, science, participation, conversations, and being seen are influencing constructs of her work. She notes that, “metaphorical representations create a ‘safe’ place for the viewer to experience a flow and connection from their interaction with the art, discovering that they are part of a bigger whole.” This intent engages a reflexivity between viewer and artist, as Ross defines her process of discovery as one that is intertwined with learning about matter itself, such as the molecular vibrations of an atom that require energy in transitions––and that everything has a frequency, which the universe reciprocates. She adds, “I paint with abandon, and my belief system is that we’re all connected through the vibrational energy of the earth that is natural.”

Change is a catalyst in her work. Ross acknowledges that it can be a simple “Aha” moment and cites that change is in the magic created within the mystery of living life––a paradigm shift.

“I change moment-by-moment. My life is an illusion that I create. My ‘what is’ is right now. I don’t paint based on what’s happening in the world. I paint what is happening within me in reaction to what’s happening in the world. A context is formed from what my subconscious needs me to expose so the art changes a perspective into a response. I have no idea what that is until the art is finished. Balanced. I start with a symbol or figure but all the rest just happens when one is put next to another over and over again.”

Watercolor is the primary media that Ross uses. The painting begins on a dry palette with infusions of pen and ink, oil and acrylic, and sometimes torn paper. Her doodles are reminiscent of Cy Twombly’s organic scribbles set in a field of lyrical abstraction. Spirals, a tonality of blended color,and metallic bejeweling embellish a framework that is grounded in graphic design and color theory. Stylized figures appear whimsical yet allegorical in a resplendent cavalcade to ignite the viewer’s attention.

The juxtaposition of semiotic imagery and magical realism creates a mise-en-scène that is metaphoric of Brecht’s theatrical alienation, in which the audience is distanced from emotional involvement by a simulated performance.

Figurative and graphic illustrations are cast as playful characters that dance across each piece with quizzical abandon. These incarnations seem to veil an angst that serves as a touchstone and catharsis for Ross, perhaps for life’s complexities. Yet ultimately, these sub-layers of existence reveal her luminous characters in a joyful expression of synergistic continuum.

Jill Thayer, Ph.D.

Jill Thayer, Ph.D. is an artist, educator, and curatorial archivist. She is Associate Professor of Art History for Allan Hancock College, Santa Maria, California; and online faculty at Santa Monica College in Art History: Global Visual Culture; Southern New Hampshire University in Humanities/Art History and Marketing; and Post University in the MBA Marketing program for the Malcolm Baldrige School of Business. Jill is contributing writer for Artvoices Magazine, Los Angeles; and Artpulse Magazine, Miami. Her postdoctoral project, “In Their Own Words: Oral Histories of CGU Art,” featuring Professors Emeritus, Professors, and Alumni of Claremont Graduate University is included in Archives of American Art at The Smithsonian Institution.

LA Artcore Exhibition 2014

Interview: Robert Seitz,

Karrie Ross lives a fully creative life, moving daily between two modes of working. As a book designer and author, with a background in advertising and marketing, she creates direct interpretations to suit the assignments she receives. As an artist with fifty years of experience with a full range of mediums, she comfortably shifts to the opposite, and works from instinct and mystery as a way to further the intense focal energy she carries within her.

Karrie Ross lives a fully creative life, moving daily between two modes of working. As a book designer and author, with a background in advertising and marketing, she creates direct interpretations to suit the assignments she receives. As an artist with fifty years of experience with a full range of mediums, she comfortably shifts to the opposite, and works from instinct and mystery as a way to further the intense focal energy she carries within her.

Her art work is about the pursuit of answerable questions. She lives for them, and frames a life through the use of questions, rules and parameters. Quite different from rules of authority where one is left only to choose obedience or rebellion, the sort of rules she discusses are more like tinkering with the instructions for playing a game. Rules introduced to increase the level of intrigue, parlay with chance, and turn a straight line into a garden path. Likewise there isn’t an absolute answer so much as call and response, diving and resurfacing beneath the waters of her search in a game of Marco Polo. She searches for an unguided answer in the work, whether it’s conscious or unconscious, and uses this to measure the degree of finish in a piece. She moves through materials and surfaces at will, and tends to take on a cluster or group of materials to work over at one time. It is as though she were an irrigation system, trying out new crops in various fields, and directing the gates of her waters in pulses that reach several ends at once.

Creating rules as she works, in the most playful sense, are key to her process. This is significant to her, she wasn’t aware of the rules (her own role in making them) when she was younger. Being aware of them means being able to manipulate them, having control over who she is, a source of growth and joy for her as she becomes increasingly familiar with how much she can direct her own perceptions.

The works have a dreamy excess to them, colors outlined with frenetic ink strokes that fizz and pop, her elements in a halo of static electricity. A visiting art critic called these marks obsessive, and in art obsession is not a liability. Spotting the grief in a particular work, Ross was delighted to hear it. Even though there is a pleasant sturdiness, a kind of holistic whimsy that characterizes their outer glow, the devil is in the details, and the pictures are raucous records of many emotions and thoughts. The artist has in reserve specific information regarding what she was going through in a particular piece, but she’s not telling, expressing the sentiment of many artists, that she’s just not interested in telling others how to see.

In the culture of art there is a prevailing interest in favoring youth. Besides the obvious paradox in reducing the visibility of skill and experience, one misses the examples of possible directions the relationship with one’s self can take. Each decade has produced leaps forward for Ross, with the current vocabulary in her work feeling as though it is just a few years old. Beyond the arch claim behind a steady incline of experience, these periodic shifts are a kind of renewal. Each time, meeting herself as a new friend, creates room for new intimacy and understanding. (end RS)

LA Artcore website interview ARCHIVED at : https://web.archive.org/web/20140826172538/ttp://www.laartcore.org/Webzine/2014/08/13/karrie-ross/

http://www.laartcore.org/Webzine/2014/08/13/karrie-ross/

IMPACT OF LIFE (catalog and video for LA Artcore August, 2014)

Review: Art Critic Shana Nys Dambrot, Art Critic

The only reason I wanted to stop and look at this particular piece is because I feel it has elements of all of the different things that I love, that are going on in other pieces throughout the whole show, but they’ve all found their way into this one image. What I mean by that is, for example, Karrie and I have been talking about this abstract figurative continuum. One of the things I love about a lot of the work is that, even though it all very clearly read as a pictorial space with objects and figures and actions, this piece, if you take out these seven little trees right there and you don’t see them, this whole expanse doesn’t even necessarily read as a horizon line anymore.

It reads as this very beautiful gestural…and this more forceful, and four to five different kinds of abstraction or abstract expressionism. Then you put these tiny, little marks a little ink, very little it couldn’t be more schematic. as far as describing a tree goes. There are a couple of them, and that’s it. Then, all of a sudden, this whole thing becomes a horizon line or a hill top.

You have this green color you read as a meadow or a grass or an natural space. You have all this stuff starting to read as a sky, weather, or atmosphere. You get this pictorial space, and all of a sudden, this egg form, it could very easily be a boulder. But you know, if you look throughout the work, that eggs are recurring imagery in the work.

All of the drawing that happens inside of it no longer takes away from it being this object that this figure is standing on. It reads clearly, “I know that there’s a lot of accidental brilliance that happened in here, and a few discoveries and things that were worked at and worked at, and then it looks simple and intuitive.”

I love this fish mostly because, if you take out just its head you don’t even have to take out the whole fish, take just head out all of a sudden, the whole thing becomes completely abstract, completely non representational. It becomes about the shapes, the colors, the textures, the tiny, tiny little mark making that’s super controlled, the splatters that are much less controlled, and those organic versus ritualistic shapes.

It takes on a completely different character, once you see the whole creature. Abstract. Fish allegory. All of a sudden, there’s narrative “What does that mean? Where does that come from?” and the symbolism that goes on in that.

Shana Nys Dambrot, Art Critic, Writer, Curate (transcribed from the show video)

Video can be seen at: https://www.karrieross.com//photos/

~Shana Nys Dambrot is an art critic, curator, and author based in Los Angeles. She is currently LA Editor for Whitehot Magazine, Arts Editor for Vs. Magazine, Contributing Editor to Art Ltd., and a contributor to the LA Weekly, Flaunt, Huffington Post, Palm Springs Life, and KCET’s Artbound. She studied Art History at Vassar College, writes loads of essays for art books and exhibition catalogs, curates one or two exhibitions each year, recently published her first work of short fiction, exhibits photography, and speaks in public with alarming frequency. An account of her activities is sometimes updated at sndx.net.

Ken Fermoyle

Conversations-2011

The Messenger, Topanga Canyon

“The expressive paintings and dialoging bustiers by Karrie Ross,are more avant garde; they both communicate and stimulate quite different messages than Andrews’ work evokes. Ross offers a selection of new work in her Spiral Series, including the new portrait series, wall hanging “Bustiers ” and more. They definitely further the promise of interaction, introspection, and informative feelings that the shows theme suggests: true conversation. And, as with Andrews’ whimsical glass pieces, there is a big helping of FUN involved!”

Ken Fermoyle

Feature Review: The Valley Scene, 2011

The Messenger, Topanga Canyon

She bills herself as “Karrie Ross, California Artist,” but the lady is much more than that. The self-proclaimed former “hippie gone wild” has also made good as an award-winning author, a book designer, a poet, fine artist, and a blogger. Blending all these talents together skillfully makes her what could be the prototype for a successful 21st Century artist.

It’s not that she uses technology to create her art, but that she is a master at using today’s tools – the Internet, websites, a blog and more – to put her work before the public. Yes, she follows the traditional path of displaying her art in galleries (she will be featured in a two-person exhibit at Topanga Canyon Gallery beginning Aug. 31), art shows and the like. But she understands today’s realities.

“Just doing the traditional things isn’t enough anymore. Fine art has universal appeal, and technologies like the Web and Internet make it possible to display it literally to the whole world.” says Ross. “That’s what I’m trying to do in my own small way.”

A 1967 graduate of Birmingham High, Ross has fond memories of “cruising the Boulevard on Wednesday nights in my boyfriend’s 1949 Chevy Coupe.” But today she’s more apt to be cruising the Internet, following up queries from her website or putting finishing touches on a new blog entry.

###