Artist Karrie Ross is a survivor.

Essay: Dave Barton, 2017

In person, you can see it in her eyes: the bright, weary glare of a woman who has been playing the boy’s club art game for more years than it’s polite to ask. I could see it in my recent studio visit with her. You can see it in the numerous works featured on her website.

Five figures—wood templates for a planned series of metal sculptures—stand in front of the window, sun bursting through the gaping holes in the middle of each, as if they’ve just faced a firing squad. Wire and bead designs hang inside the holes; Tao symbols, wheels, eggs, and flowers all standing in for viscera. In place of faces, more beaded glass gives us eyes, noses, the suggestion of a wan smile; fright wig hair springing from the heads painted to represent Wu Xing (Elements). Given a little refinement and the more solid structure that metal will bring, one can easily imagine them whirling on spinners as kinetic pieces.

The ONE: 4″x4″ canvas’ collage images with The ONE removed out on a stick to be inserted by hand in perspective and participation

Other idiosyncratic figures, still alone, but grouped together in The ONE: Boxed, looking like solid bricks in a wall. The more than a dozen small boxes, exquisite corpses covered with vibrant card art created by another artist and repurposed by Ross, feature a lone figure attached at the top or side. Solitary, defiant, the planted figure often defying gravity, and never too far away from its origin: Cut from the front of the card art, it has left a bright and beautiful Hiroshima shadow underneath.

That lonely figure standing amid a chaotic background is a continuing theme in her latest works on paper. In Nature: The ONE with Water, the armless figure stands in water, towering high above the tiny wave breaks below. Her tapering neck—bright, lightbulb head glowing gold—sways and bends dangerously as the paint-spattered wind whips her about, her trunk, filled with a visible brown miasmic grief, firmly rooted in place.

In another, Where is the Water?, a smaller figure is seen buried from the waist up (ala Samuel Beckett’s Winnie in Happy Days) in a similar watery. Assailed from above by flying, pizza slice-shaped darts—some aimed at her, others seemingly deflected by her circular wings—she still glows, a silver statue of strength.

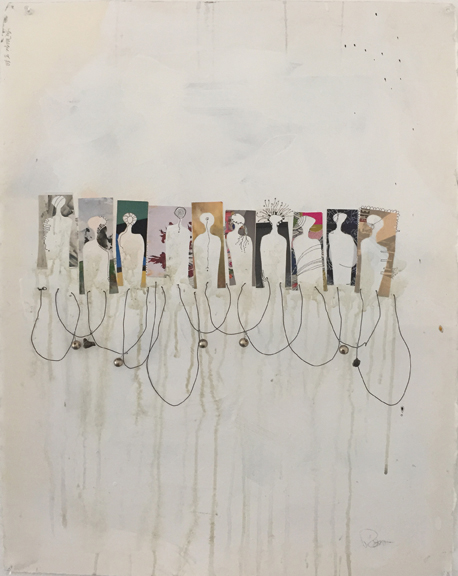

In the mixed-media The Magic of Ten, ten of the outlined figures stand in an uneven row against a background of dripped paint that looks like a combination of watery mold and running mascara. Instead of a single figure going it alone, Ross has linked the figures with wire, making them more of a chain gang, suggesting strength through a united front.

Being targeted by the slings and arrows of life covers a lot of artistic ground for many artists: the fears of not being seen; the long hours in a studio by oneself; the accompanying depression that comes with never making quite enough money doing what you love; having to take meaningless side gigs to make ends meet. It can feel like one is continually beset.

Ross’ work is a grand statement that she’s around, fighting, despite what life has handed out to her (and us, by extension). Instead of being crushed under that weight—as so many of us have—she is extending an open hand, and saying stand up, come with me, we’re safer in numbers.

Dave Barton Has interviewed artists from punk rock photographer Edward Colver to monologist Mike Daisey, playwright Joe Penhall to culture jammer Ron English. He writes art reviews for the OC Weekly for over twenty years, the last eight as their lead art critic.